An extract from a biography that will never be written

The dough slapped against the metal tray. She massaged the pliant goop, gathering it and forcing it against the tray, spreading and kneading it with her hands. Her moist skin shone like red leather as she worked the dough into a saucer shape and slapped it onto the hot tava, her sari coiling in the draft. Above the sizzle, she heard fast running footsteps and looked through the door to see her boy hurry past.

“Pattabhi!”

The boy returned and stood, framed by the morning light: 12 years-old, knobbly-kneed and gangly-armed. He was wearing a white doti and clay-coloured shirt. His wispy, dark hair was combed flat against his head and, while his eyes were wide as a child, his lips curled in the faint smirk of young manhood. He was impatient and shuffled from side to side as his mother appraised him.

“Where are you going?”

“To a show, mum.”

“What show? Where?”

“Hassan, mum. There is a siddha coming to give a demonstration. They say he can bend metal with his bare hands.”

“And how much will this devilry cost, eh?”

“It’s free for students if we stand at the side and promise to be quiet.” Pattabhi Jois spoke with an earnestness that touched his mother. He was getting harder to keep track of these days, she thought. Always running here and there with his friends. She didn’t reply. Just tore another portion of dough, pressed it between her hands and slapped it on the frying pan. When she looked up, Jois was gone.

He walked at a fast pace on the main road out of Kowshika, his home village of 70 families, towards Hassan, the nearest town. Hassan was and still is the name of a town and district in Karnataka, South India. At this time the population would not have grown much since the 1901 census pegged it at 8241.

It was a familiar walk. He made it every day to attend school in Hassan. A ninety-minute trudge, slightly uphill. The road was made of compacted red earth and its surface was gnarled and full of potholes. It was November and the rainy season was finishing. Luminous green rice paddies stretched into the blue mountains in the distance. The scent of jasmine came from the bushes on the side of the road and palm trees with their great, dreadlocked branches offered some shade from morning sun. He walked barefoot and purposeful.

Jois, deep eyed and excited, hustled down the crowded street. Single and two-storied buildings lined the dirt road, some with brown thatched roofs, others in tumbledown terracotta. Vegetable sellers squatted over baskets of lentils. Mud walls mingled with modern brick buildings. After the heavy rains, older buildings have slipped and their walls now stood at strange angles, some needed to be propped up with thick wooden beams. Jois wound past cow-dragged carts and rainbowing saris – women with wide hips and clay pots on their heads, brass and silver bangles tinkling on their wrists. Beggars prostrated on the ground, wrapped in dirty cloths and semi-wild dogs tussled in the shade erupting into barks and snarls. Traders, hawk-eyed and strutting outside their shops and stalls, called out, “Hey lady! Hey boy!”Jois smiled at the traders and hurried on, stopping only at a wooden stall where a woman in a violet sari presided over a pan of volcanic oil where donut-shaped vadas – lentil flour cakes – floated like rubber ducks at a fairground.

“Yes, youngster, what do you want?” The woman’s husband was doing front of house.

“One vada, please.” The man’s curled moustache twitched and he hooked Patthabi’s prize and plonked it in a palm leaf.

It tasted of oil and cumin and Pattabhi squatted by the side of the road, eating his breakfast, watching the throng of people file into Jubilee Hall – a single-story brick building with a hand-painted poster outside which read, “Witness the great sage and his powers! The man who can stop his own heartbeat!” He screwed up the palm leaf and threw it in the gutter and squeezed past the crowd to stand with the other young boys at the side.

Jois recollected towards the end of his life that the demonstration was organized by local official who was interested in yoga. “[He was] a deputy commissioner who was a Muslim… I can’t remember his name… good man, good man, he had a good samskara, and he encouraged yoga a great deal.”[1]

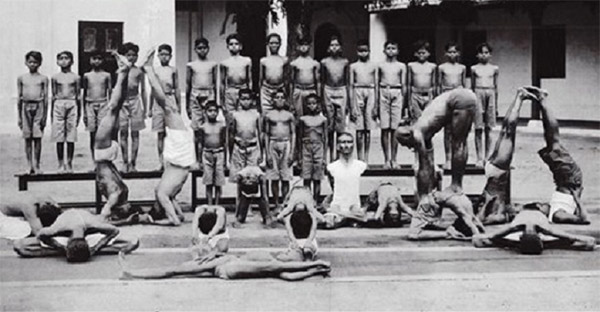

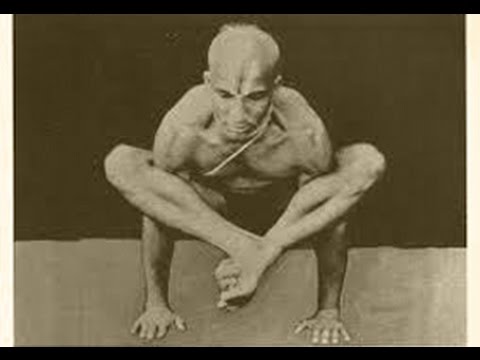

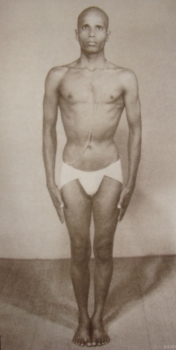

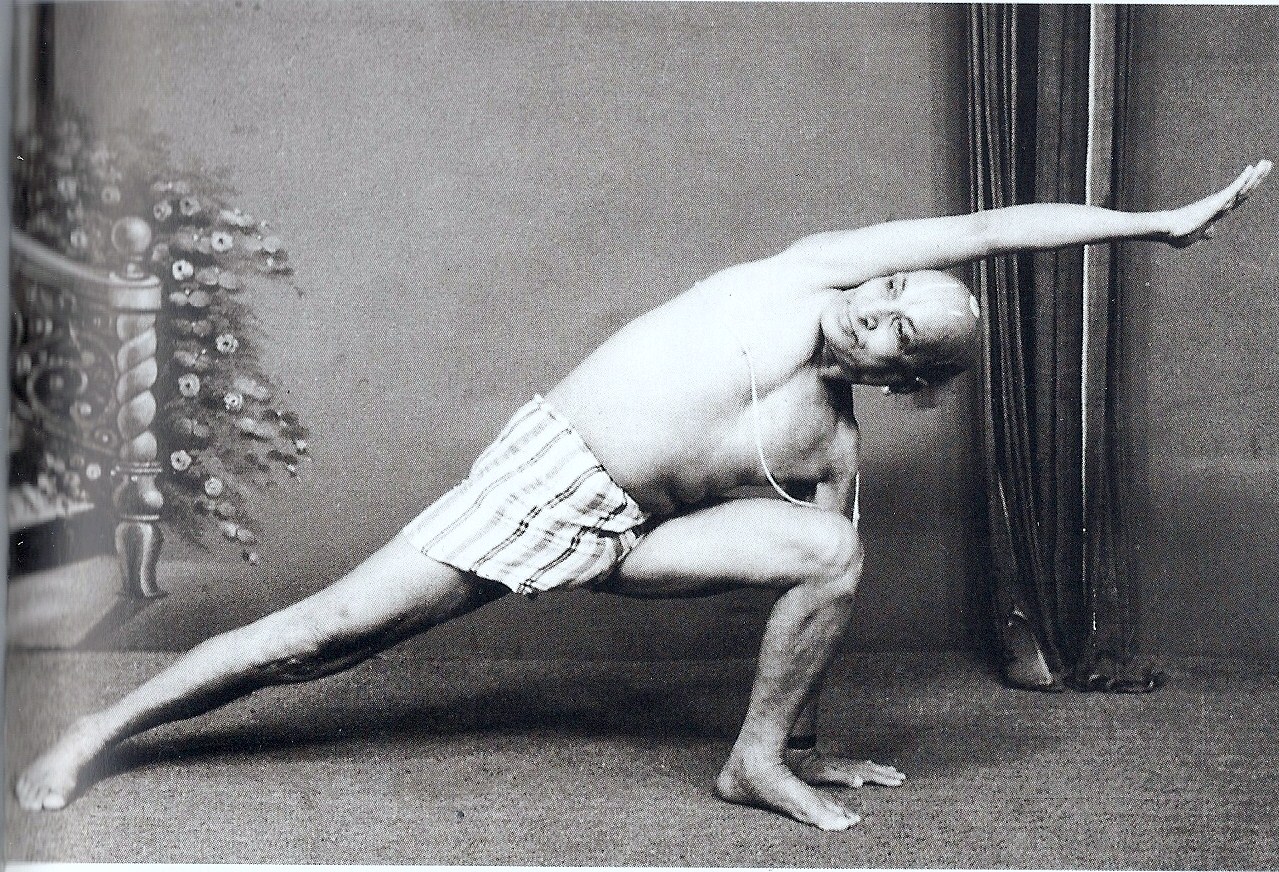

Krishnamacharya, the sage, advanced on the crowd from the back of the stage. He stood before them wearing only a loincloth – five feet and two inches of taught muscle. We can imagine a silence falling on the crowd as the sage stood, waiting for the hubbub to die down. Despite his diminutive size he commanded respect, even fear in others. “Krishnamacharya’s manner was intimidating even while he was standing still,”[2] said researcher, Elliot Goldberg. While yoga legend and former student, B. K. S. Iyengar, remembered that “people would walk on the left footpath if he was on the right side.”[3]

The sage stood with a rigid back, shoulders perfectly square, his eyes were steady and his powerful gaze projected years of study and practice in the best schools in the country and, if legend is to be believed, seven years with a Tibetan yoga master. He began to speak in a clear, confident voice, perhaps answering common questions like, “Why should yogaabhyasa be done? What does one gain as a result of practising yoga? What should the duration of the practice be? How much time should be spent on the practice? What are the reasons for and effects of the practice?”[4]

After speaking for a short time, he stood on a rug that covered the wooden stage. “This is mayurasana,[peacock pose]” he said. He touched the ground, lifted his legs as if they were featherweight and came to perfect balance with hands on the floor, elbows pressing into his abdomen, his body taught and smooth. Impressive noises and gasps rippled through the crowd. After a few minutes he leapt to his feet again. He likely followed up this demonstration by extolling the benefits of the pose. “It will protect us from every disease and keep these diseases from approaching. We can say that it is the death of all respiratory diseases, all paralytic diseases — all such dangerous diseases. No disease will approach the people who practice this asana.”[5]

While mayurasana has a long history of use in yoga tradition and would have likely featured in his demonstration, the exact content of his Jubilee Hall display can’t be ascertained. What is certain is that whatever 12-year-old Jois saw that day altered the rest of his life, would lead him to find one of the most influential yoga schools in the world, and make him and his family rich. In fact, it’s even possible that if Jois had missed that demonstration then the Ashtanga, Vinyasa Flow and Power Yoga classes that proliferate the world today might not exist.

In the 1920s, Krishnamacharya gave demonstrations and lectures throughout Karnataka to arouse interest in yoga which, in those days, was looked upon as an activity only fit for drop-outs and ruffians. “Krishnamacharya sought to popularise yoga by demonstrating the siddhis, the supernormal abilities of the yogic body. These demonstrations, designed to stimulate interest in a dying tradition, included suspending his pulse, stopping cars with his bare hands, performing difficult asanas, and lifting heavy objects with his teeth.”[6] When Jois disciples, Petri Räisänen and Eddie Stern asked an elderly Jois what he saw at this pivotal moment all he remembered was being deeply impressed with how Krishnamacharya “jumped from asana to asana.” So impressed, in fact, that Jois sought out the sage the very next day beginning a guru–shishya relationship that would last 25 years. “I studied with [Krishnamacharya] from 1927 to 1953. The first time I saw him was in November of 1927. … I found out where he lived and went to his house. He asked me many questions, but finally accepted me and told me to come back the next morning.”[7]

At that time, Krishnamacharya was struggling to transition to household life after spending most of his life studying or living as a semi-renunciate in the Himalayas. A blisteringly bright scholar, he had travelled to the great universities in Benares (Vārānasī), Bihar and Bengal and held degrees in each of the six Vedic darśanas – schools of philosophy. He was also a healer and musician according to his son and student, Kausthub Desikachar. “He was also a master of Ayurveda. He used to prepare Ayurvedic medicines and herbal oils … Besides mastery in the fine art of music … [he] was a wonderful cook.”[8]

Exactly where and how Krishnamacharya learned asana, pranayama and the ability to stop his heartbeat is hotly debated. The orthodox legend is that he learned asana, pranayama and the moving meditation that formed the basis of his early teaching: vinyasa, from a cave-dwelling yogi named Rammohan Brahmacari. He studied with this guru near Lake Mansarovar in Tibet for seven years. “What were the studies in the cave? I know they embraced all of the philosophy and mental science of yoga, its use in diagnosing and treating the ill; and the practice and perfection of asana and pranayama,” said Desikachar.[9] Krishnamacharya learned to recite the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali by heart and, according to Jois, a lost text known as the Yoga Korunta which contained instructions on how to perform vinyasa – a cornerstone of Krishnamacharya and Jois’ teachings. Author and student of Jois, Eddie Stern reported that Jois was fond of quoting a verse from the Yoga Korunta: “When doing yoga, do not do the many types of asanas without the use of vinyasa.”[10]

However, researchers dispute this story. Goldberg said, “It’s likely that most if not all of Krishnamacharya’s account of his discipleship is fabricated.”[11] While scholar Mark Singleton notes that “mischievousness with regard to his own history, combined with the sometimes creatively hagiographical accounts of his recent biographers, makes it difficult to offer a definitive version of [Krishnamacharya’s] life.”[12] His story of studying in Tibet is impossible to verify today. My own opinion is that it’s more likely he learned from one or more Tibetan yogis. Here’s why.

When Krishnamacharya returned to Mysore, he was giving demonstrations featuring advanced asana, pranayama and feats of strength and physical control that he could not have gleaned from his Brahminical and university education, especially the ability to stop his heartbeat which was verified by two doctors at the time[13] and which is an esoteric technique that far more resembles the tantric and Hatha Yoga lineages of North India, Nepal and Tibet. Furthermore, his mastery of asana was complete or he would not have been able to wow audiences and swiftly become the top yoga teacher in Mysore. Such a mastery would have taken years of training under an experienced teacher. Where else but in the Himalayas would he have found the expertise and time to perfect such esoteric and rare techniques?

Some versions of Krishnamacharya’s life story mention that he taught pranayama to Lord Irwin before going to Tibet. “With the help of yoga [read: pranayama], Krishnamacharya had cured Lord Irwin, the then Viceroy of Simla, of diabetes. In return, the Lord sponsored his trip to Tibet in 1919.”[14] So far no records verifying this have been found. However, it seems unlikely that a British official would have taken medical advice from an unknown local given the disparaging attitude of British officials towards indigenous knowledge.

If we are to believe that his studies in Tibet really were fabricated, Krishnamacharya would have had to learn pranayama from one of his Brahminical academic tutors and developed his mastery of asanas and other esoteric techniques completely by himself in some unknown location. It’s unlikely. Especially given that prevailing attitudes in the universities at the time were pretty anti-yoga. While Goldberg and others cite the fact that Krishnamacharya’s accounts of the time don’t add up, I think this is most likely down to the fact he was interviewed in his dotage and the sage was reluctant to say anything aggrandising.

Whatever the case, he returned to Mysore an accomplished scholar and yoga master. Upon his return he married a 12-year-old girl called Namagiriamma, the sister of B. K. S. Iyengar who would later become a student of Krishnamacharya and go on to have a massive influence on yoga and physical culture in the 20th Century. Namagiriamma would have been ordered to marry the stern 37-year-old and had little say in the matter. Although it was typical in the culture of the day, the marriage would have been illegal had it happened just a few years later according to researcher, Hilary Amster. “As far back as 1929, the Indian Parliament (at that time under the control of the British), pressured by certain members of society, recognized and attempted to act against the horrors of the social custom of child marriage.”[15] Like many women of her day, facts about Namagiriamma are thin on the ground. “There is a saying that behind every great man, there is a greater woman,” said their son, Desikachar in his biography of his father. “Namagiriamma was Krishnamacharya’s dedicated partner in life and in his mission to preserve and spread the teachings of yoga. Though she was a very quiet person, her support of Krishnamacharya was always unquestionable.”[16]

Krishnamacharya is noted for teaching yoga to women which at the time was thought to be very radical. Indeed, there is footage of Namagiriamma practicing advanced asanas in a 1938 silent movie of Kirshnamacharya and his family.[17] However, every one of his students have noted how Krishnamachrya was strict and harsh especially in his early years. Patthabi Jois later recounted how he beat his students for making mistakes saying, “He would beat us. And the beating was unbearable.”[18] Whatever their marriage became, the prospect of marrying a 37-year-old man must have been terrifying for the young Namagiriamma, let alone someone as imperious as Krishnamacharya.

Struggling to support himself and his new wife, Krishnamacharya was forced to take a job as the foreman of a coffee plantation which is why he was living in Hassan. Coffee cultivation was introduced to the area by the British in 1843 and was a growth industry at the time. However, it was far from lucrative and “the couple lived in such deep poverty that Krishnamacharya wore a loincloth sewn of fabric torn from his spouse’s sari.”[19] Goldberg quotes B. K. S. Iyengar who said, “It was unimaginable to see a man dressed in such a manner who had studied Sad-darsanas [six systems of Indian philosophy].”[20] Despite his difficulties, Krishnamacharya was keen to give yoga demonstrations in his spare time and even teach students in the early mornings. Students like young Jois.

The Monday after the demonstration at Jubilee Hall, Jois got up as soon as the cockerels began crowing around 4am. He rolled up his blanket and stepped around the sleeping bodies of his parents and six siblings. (His parents would eventually have nine children; Jois was the fifth.) Outside, the earth felt cool on his bare feet. The air vibrated with the sound of crickets and croaking frogs. Cows shuffled in the shed. He went to the huge ceramic urns behind the house that held the family’s water and filled a bowl in the moonlight. He splashed chilly water on his face and rubbed the sleep from his eyes. Wearing his usual doti and shirt, he trotted off in the direction of Hassan to begin his yoga studies before school.

We don’t know the exact content of Krishnamacharya’s yoga curriculum in 1927. The best source for his early teachings is found in his book Yoga Makaranda published in 1934. It’s reasonable to assume he was teaching a proto-version of what he presents in that text during his stint in Hassan. The text outlines Patanjali’s eight-limbed yoga with an emphasis on asanas linked by flowing movements known as vinyasas. In his old age, Jois mentioned his earliest studies in Hassan as consisting chiefly of asana and pranayama.[21] In another interview, Jois said, “[Krishnamacharya] agreed to teach me, and we started from the next day. By the time he taught us ten asanas.”[22] In other interviews, Jois mentions learning texts such as the Yoga Sutras, Bhagavad Gita, Yoga Vasishta and Yoga Yajnavalkya though this is likely a feature of his later studies at the Sanskrit college and Mysore Palace. Krishnamacharya was known to have his young students recite mantras in poses as a way of keeping their attention from wondering.[23] He may have been using this technique when Jois began his studies with him.

It’ss likely that Jois first learned a handful of asanas in a specific sequence. According to Desikachar, “In the beginning of [Krishnamachrya’s] teaching, around 1932, he evolved a list of postures leading towards a particular posture, and coming away from it.”[24] Krishnamacharya wrote Yoga Makaranda in 1933 and it no doubt represented the apex of several years of teaching and practice up to that point so it makes sense that the core teachings therein were imparted to young Jois at least in proto form on those chilly Hassan mornings. Indeed, it seems that the modern style of yoga teaching, in which poses are often arranged in a sequence flowing from one pose to another, was present in Krishnamacharya’s teaching way back in 1927.

Krishnamacharya’s house was still in shadows when Jois arrived. The sun was peeping over the horizon making the sky glow the colours of peeled prawns and papaya flesh. There was a faint glow coming through the muslin-covered windows. In the darkness, the house looked warped and unwelcoming. Jois took a deep breath, knocked once, and then again, just in case. The sage swung the door open and glared at the thin boy. He held a brass pocket watch in his hand and turned the clockface to Jois.

“You’re two minutes late.” Jois bowed.

“I’m sorry, sir.”

“If you arrive late again don’t ever come back here… Laziness!” He spat the word out like poison. Then he quoted the Dattātreyayogaśāstra in perfect Sanskrit. “[If] diligent, everyone, even the young or the old or the diseased, gradually obtains success in yoga through practice.”[25] Reverting back to their shared Kannada language, the older man drilled home his point. “See, boy, diligence is key! I don’t ask you for any donation, do I? Only diligence and effort. Now, come inside.”

The small house only had two rooms and a cooking area outside where Namagiriamma was already awake, preparing rotis. The smell of warm ghee made Jois’ stomach rumble. Krishnamacharya walked into a plain room containing a desk, chair and a cheap rug for practising asana.

“Stand here.” The master said, gesturing at the carpet. “No, not like that.” He leapt upon Pattabhi, seizing him by the shoulders and pulling them back. “Straight back, chin back, legs together and toes touching.” Jois did his best to accommodate the gruff instructions and adjusted himself until the master was satisfied. “Good,” he said. “This is tadasana [mountain pose]. Prepare to recite the mantra.” Krishnamacharya inhaled and intoned in Sanskrit: Jivamani Bhrajatphana sahasra vidhdhrt vishvam Bharamandalaya anantaya nagarajaya namaha (We open ourselves to the energy of this practice and offer gratitude for the guidance of the teachings of Yoga on the path to Self-discovery – through the body, the breath, and the meditative mind).[26] Jois repeated the mantra.

“Your pronunciation is not bad. Your father has been teaching you I see.” This was the nearest Jois would be to receiving a compliment from his teacher for the next two years. “Now, inhale deeply,” Krishnamacharya continued. “Keep going, yes, now hold the breath.” Jois did so. “Good,” the master continued. “Now exhale slowly, bend over and put your hands on the floor – don’t bend your knees! Legs straight. Exhale completely. Now stay there. Breathe!”

While some of the poses recognisable today such as Surya Namaskar may have featured in Jois’ early lessons, it’s unlikely. Krishnamacharya started teaching Surya Namaskar as a sequence some years later during his stint teaching at the Mysore palace.[27] The sequence does not feature in Yoga Makaranda. The poses of Surya Namaskar are there but they are not treated as a sequence. Furthermore, in that text, Krishnamacharya includes breath-holds (kumbhakas) and encourages contemplation of “The Divine” neither of which featured in presentations of Surya Namaskar circa 1927.

“Now, return to tadasana.” Krishnamacharya continued. Jois returned to the first pose, standing to attention. “Now, jump your feet apart. Land lightly not like an elephant! Clasp your hands together behind your back. No, like this.” He gripped Pattabhi’s hands behind his back as if handcuffing him. He squeezed his palms together and manoeuvred his fingers so they interlaced. “Now, turn to the left and exhale slowly. Put your face on your kneecap.” Jois’ head hovered slightly above his kneecap. His hamstrings wouldn’t stretch enough for him to reach the target. He felt Krishnamacharya’s cold grip on the back of his neck, forcing his head down until it touched his knee. Jois leg started trembling. “Relax and breathe,” was all the master said. Eventually the master allowed the boy to return to standing before forcing him down on the other side.

“Return to tadasana.” Jois did so, his breath quick, his pulse raised. “Calm yourself, young man.” The master said. “This next pose is very old and very auspicious. Take your right foot and place it high on your left thigh. This is a half lotus. Take your right hand around the back.” Krishnamacharya grabbed Jois wrist and pulled his hand behind his back so he could grasp the foot. Luckily the long-armed youngster could easily reach. “Yes, balance there,” the master said. “Did you father teach you the 108 names of Lord Krishna?” The master paused to pick up a thin cane he had left by his desk.

“He did, sir,” Jois replied.

“Good, now hold this pose and chant the names. Focus on God.” Jois began, his high unbroken voice ringing out in earnest, “Om Shri Krishnaya Namaha, Om Kamala Nathaya Namaha…”

Every time his mispronounced a syllable Krishnamacharya whacked him across his shoulders with the cane, making Jois wobble and nearly loose his balance. “Again! Repeat.” It was standard practice in those days to beat lessons into children and neither would have questioned the technique. Krishnamacharya was reportedly so fierce that a number of his students dropped out, apart from Jois whose devotion and enthusiasm for yoga was so strong, even at this early stage, he carried on “unmindful of the beatings.”[28] After Jois completed his recitations standing on his left leg holding his right in half lotus, Krishnamacharya ordered him to change sides and repeat the mantra standing on his left leg.

The muslin-covered window glowed with sunlight as Jois rose up from child’s pose, steady-eyed and determined, sweat cooling on his forehead.

“Now we begin pranayama,” Krishnamacharya said. “Inhale to my count, 1… 2… 3…” he tapped out the rhythm on the floor using his cane. “Now exhale 1… 2… 3…” After a few rounds of slow breathing he ended the lesson with a mantra from the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad. “Om asato mā sad gamaya tamaso mā jyotir gamaya mṛtyor mā amṛtaṁ gamaya om śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ.”[29] Jois’ family were Smarta Brahmins and chances are he would have already known this famous verse from his studies with his father. He chanted along; his pronunciation was good enough to avoid further whacks from Krishnamacharya’s cane.

The minute they were finished Namagiriamma entered as if she had been skulking outside waiting. Face down and fearful, she set a tray of rotis and dhal on the desk. Namagiriamma, a thin girl in a spotless sari, brass bangles jingling, her reddish-brown skin peppered with jewellery in her nose and earlobes.

“Woman, bring some food for the boy,” Krishnamacharya said. The girl scurried out and returned with another tray of roti and dhal for Jois. The boy sat on the floor and the master at his desk. They ate in silence. After he ate, Jois thanked his new guru by prostrating before him, flat on the floor his arms outstretched. Krishnamacharya nodded in response.

It was nearly time for school when Jois left. The small town was already alive with oxcarts, women carrying water, officials marching and dogs barking. Jois was transfixed in a post-yoga glow. For a moment or two he was certain he saw the power of Brahma pulsating. He felt and saw prana flowing: half gold, half liquid, it enfolded and danced around the arcadian scene before him. A sense of pure gratitude welled up within him. He turned back to Krishnamacharya’s house to give one final salutation when he noticed the door open. A shabby man exited, dressed like an agricultural worker in baggy trousers and a straw hat with a wide brim. Was this really his guru? Krishnamacharya didn’t notice his student staring. The master turned, and with all the pride he could muster, strode down the dirt road towards the coffee plantation.

[1] JOIS (2006) Interviewed by EDDIE STERN. Available at: https://yogidelicious.com/wordpress/how-pattabhi-jois-learned-yoga-from-krishnamacharya-from-interviews/

[2] GOLDBERG, (2016) The Path of Modern Yoga. Inner Traditions, USA

[3] IYENGAR, (1978) Body the Shrine, Yoga Thy Light, quoted in GOLDBERG (2016)

[4] KRISHNAMACHRYA (1934) Yoga Makaranda.Madurai C.M.V. Press, India

[5] Ibid.

[6] RUIZ, (2017) Yoga Journal. Available at: https://www.yogajournal.com/yoga-101/krishnamacharya-s-legacy

[7] JOIS (2004) Interviewed by R. ALEXANDER MEDIN for Namarupa. available at: https://www.yogastudies.org/wp-content/uploads/3_gurus_48_questions.pdf

[8]DESIKACHAR (2011) Yoga of the Yogi. North Point Press, USA

[9] DESIKACHAR (2011) Health, Healing, and Beyond: Yoga and the Living Tradition of T. Krishnamacharya. North Point Press, USA.

[10] STERN (2019) One Simple Thing: A New Look at the Science of Yoga and How It Can Transform Your Life. North Point Press, USA

[11] GOLDBERG, (2016) The Path of Modern Yoga. Inner Traditions, USA

[12] SINGLETON & FRASER (2014) Gurus of Modern Yoga. Oxford University Press, UK

[13] HAMBLIN (2014) Dead or Meditating? In The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/05/dead-or-meditating/371846/

[14] INDIA TODAY STAFF (2016) 7 interesting facts on the Father of Modern Yoga, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya available at: https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/yoga-teacher-839074-2016-11-18

[15] AMSTER (2009) Child Marriage in India. University of San Francisco School of Law, USA

[16] DESIKACHAR (2011) Yoga of the Yogi. North Point Press, USA

[17] Unknown source. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ML9yZd7bIvY

[18] JOIS (2006) Interviewed by EDDIE STERN. Available at: https://yogidelicious.com/wordpress/how-pattabhi-jois-learned-yoga-from-krishnamacharya-from-interviews/

[19] RUIZ, (2017) Yoga Journal. Available at: https://www.yogajournal.com/yoga-101/krishnamacharya-s-legacy

[20] GOLDBERG, (2016) The Path of Modern Yoga. Inner Traditions, USA

[21] ANDERSON (1994) An Interview with K Pattabhi Jois: Practice Makes Perfect. Yoga and Joyful Living Magazine. Himalayan Institute

[22] JOIS (2006) Interviewed by EDDIE STERN. Available at: https://yogidelicious.com/wordpress/how-pattabhi-jois-learned-yoga-from-krishnamacharya-from-interviews/

[23] SCHMIDT-GARRE (director) (2013) Breath of the Gods [documentary movie]. PARS Media, Germany

[24] DESIKACHAR from Lectures on ‘The Yoga of T Krishnamacharya given at Zinal, Switzerland 1981. Available at: https://yogastudies.org/category/cys-journal/sampradaya-posts/desikachar-seminars/yoga-of-t-krishnamacharya/page/2/

[25] MALLISON (2013) Dattātreya’s Discourse on Yoga. Unpublished. Available at: https://terebess.hu/keletkultinfo/lexikon/Datta-Mallinson.pdf

[26] Translation unknown. Available at: http://yogastha.com/The-Philosophy/The-Practice/Training-Info/Sutras—Mantras/sutras—mantras.html

[27] SINGLETON (2010) Yoga Body. Oxford University Press, USA

[28] JOIS (2006) Interviewed by EDDIE STERN. Available at: https://yogidelicious.com/wordpress/how-pattabhi-jois-learned-yoga-from-krishnamacharya-from-interviews/

[29] Translation unknown. Available at: http://yogastha.com/The-Philosophy/The-Practice/Training-Info/Sutras—Mantras/sutras—mantras.html

I was having second thoughts about this very good this post knowledge is always welcome this site only has interesting articles.

Your website is amazing congratulations, visit mine too:

https://b9g.net

.